Dancing

Dancing

When I was seven I saw my first balletperformance in a real theatre.

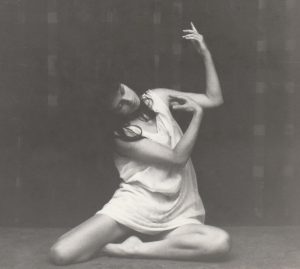

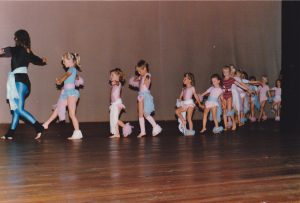

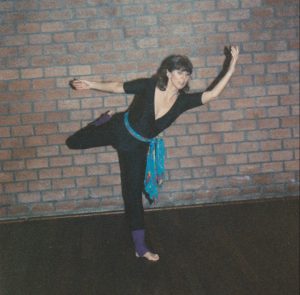

I remember red chairs, dark red velvet curtains and the typical smell of perfumes, dust, and the murmuring of soft voices. Then the lights went off and everybody was quiet.It started with todlers, turning around, jumping, running, standing still and sometimes waving to their parents in the front rows. Most exciting were children my age who were real ‘ballerina’s making pirouettes, tendu’s, and arabesques although I didn’t know those terms at that time.But I knew immediately: ‘ this is what I want to do myself, ‘It had the same magic as the flowerfairies from Mary Cicely Barker. So I started classical ballet at age nine and I have never stopped dancing since. Dancing also plays an important role in ‘the Golden Light of Africa.

Fragmentfrom the Golden Light of Africa (137, 138)

The band begins to play a medley of jazz and South American music. Within five minutes the floor is full of rocking, swinging and hip-swaying Africans, Indians and whites.

I throw myself whole-heartedly into the dancing throng. The thin skirt swirls about my legs and the shell necklace swings with it. Dancing for me is like breathing. That’s always been so, ever since I was seven, when I went to the theatre for the first time for a local ballet school performance. To dance, to float, to sway, to leap and turn, that’s what I wanted. Like the flower fairies in the English book.

Evening, dear, and how-d’ye-do?

I turn round with a start. Sven is standing before me, stylishly dressed in black jeans and snow-white shirt. I’m hardly surprised. On a fairy-tale day like this anything can be expected.

‘I told you we would meet again.’

‘Flower Fairies.’

‘Flower Fairies.’

When I was six , my eldest sister went abroad to improve her English. Coming back, she showed me a little booklet and translated the English poems for me. The enchanting pictures from singing and flying creatures amongst bright coloured flowers, snails, grasshoppers, bees, and mice made a deep impression on me.

Fragment of the Golden Light of Africa. (page 67-68)

‘Will you read me a story?’ Her small hands pick up the children’s book.

‘That’s English. You won’t understand it.’ But my daughter, who’s already stuck the bedtime-story thumb in her mouth, lisps ‘Yeth I will.’ With the rustling of eucalyptus trees and the croaking of birds of prey in the background, I start to read.

You come with the Spring, O swallow on high!

Almost twenty years ago I lay in the narrow bed of my big sister, who worked as an au pair in England, and who read to me from the same book. The flower in the illustration looks like the buttercups in front of our house. Sasja notices that as well and says, still lisping because of the thumb, pointing with the other hand to the margarine tin: ‘Thoth are the thame.’ I read on.

Almost twenty years ago I lay in the narrow bed of my big sister, who worked as an au pair in England, and who read to me from the same book. The flower in the illustration looks like the buttercups in front of our house. Sasja notices that as well and says, still lisping because of the thumb, pointing with the other hand to the margarine tin: ‘Thoth are the thame.’ I read on.

Your nest, I know, is under the eaves;

While far below, are my flowers and leaves.

With that mental image of myself as a little girl in that bed, a wave of homesickness, mixed with panic, surges through me. I would like to call ‘Mummy, Mummy, Mummy!’ and know that everything will be all right. But Sasja gives me no chance to sink into nostalgic reflection and commands: ‘Now talk proper!’

Regaining control of myself, I try to translate the English into Dutch, hearing myself stumbling and searching for the right words, just as my big sister had done for me in the old days. At the age of six, I’d never had anything to do with far countries and foreign languages.

Regaining control of myself, I try to translate the English into Dutch, hearing myself stumbling and searching for the right words, just as my big sister had done for me in the old days. At the age of six, I’d never had anything to do with far countries and foreign languages.

They seemed on a par with the Lands Where the Jumblies Live, peopled by strange folk, with strange children who spoke a strange language. At all events, the whole business was something very far away. England, Paulien had said.

A land where winged elves lived, that’s what my child’s mind made of it. England then seemed like the end of the world. About as far away as a six-year-old could imagine…